We have now reached the end of the course HEDS241, and in this final individual reflection I will look back on what I have learned this semester. I will also look forward, reflecting on how I can use the competences from this course in my own teaching.

- What are the

most important things that you have learnt through your engagement in this

course? Why?

The most important things

I have been introduced to in this course are the critical perspectives on

education, universities, and sustainability education such as for instance

Osberg, D. and Biesta, G. (2020), Lotz-Sisitka et al. (2015), Stein et al (2022),

Orr 1991, It has been a comfort to know that I am not alone in thinking that

the educational system is not doing what it preaches in terms of

sustainability, and that we as educators are not giving students the competence

they need concerning sustainability. For me it is important to acknowledge our

shortcomings and mistakes before we can move on and do something about the

problem.

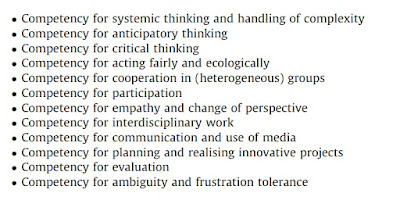

I also found it very interesting to learn about

all the different views on sustainability (Hopwood et al 2005). This helped me

understand and interpret discussions I have had with others about

sustainability. I also thought it was interesting to read some of the research

concerning sustainability competences, and I especially liked the competence

models that included implementation competency, such as Brundiers et al.,

2021).

The models for sustainability didactics for higher

education was what motivated me to take this course in the first place, and I

did learn a lot about this topic. For instance, I learned that there are

different approaches or teaching styles concerning sustainability education;

normative, fact-based and pluralistic (Öhman and Östman, 2019). The pluralistic

approach treats sustainability questions as political problems, where people

might agree on the facts, but can have different ideas to how to solve the problem.

The pluralistic tradition has been found to be the most promising way

forward.

We also learned about several different

pluralistic didactic models for teaching sustainability, such as Constructive

alignment and Tree of Science (Wilhelm et al., 2019), Wicked problems (Block et

al., 2019), Sustainability commitment (Öhman & Sund, 2021), and finally

Five forms of democratic participation (Lundegård & Caiman, 2019). I

preferred the last one, as it resonates with my own teaching philosophy of

student activity and participation.

· How will your learning influence your practice?

I liked the pluralistic

approach to sustainability education, and especially the the five forms of

democratic participation-model. Without having had a name for it, I think that

my teaching has been moving in this direction for a while. For instance I try

to choose authentic learning situations that give room for student agency and

creativity, as well as giving room for deliberate discussions and critical

reflection. However I still have a lot of work to do here concerning

creating authentic learning situations. I also think I should make the didactic

choices explicit for the students, especially since they are teacher students

and it is important for them to reflect on didactics.

· What are your

thoughts about didactics for sustainability in your

own context?

As a teacher educator, I think that I

have more questions concerning sustainability didactics now, than I had before

the course. Some of the questions I have are; What is the relation between the

didactics in higher education and didactics that teachers use in school? Is it

the same, or different? Do we need a special type of didactics in teacher

education to give teacher students the type of educator competences that they

need to teach their students about sustainability? Or can I teach my teacher

students the Five forms of democratic participation, so that they can use them

with their pupils?

· What are you going to

do as a result of your involvement in this course? Why?

This course has made

me reflect on my own responsibility concerning teaching sustainability. As I

mainly teach chemistry and science didactics for teacher students, I have felt

that sustainability is not really my responsibility. However, some of the readings

we have done for this course has made me rethink this.

|

| Figure: Chemical hazard symbol for environmental danger. |

Sources:

Block, T., Van Poeck, K.,

& Östman, L. (2019). Tackling wicked problems in teaching and learning.

Sustainability issues as knowledge, ethical and political challenges. In

Sustainable Development Teaching (1st ed., pp. 28–39). Routledge.

https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351124348-3

Brundiers, K., Barth, M.,

Cebrián, G. et al. (2021) Key competencies in sustainability in higher

education—toward an agreed-upon reference framework. Sustain Sci 16,

13–29.

Hopwood, B., Mellor, M.,

and O’Brien, G. (2005). Sustainable development: mapping different

approaches. Sustainable Development, 13(1):38–52.

Lotz-Sisitka, H., Wals, A.

E., Kronlid, D., and McGarry, D. (2015). Transformative, transgressive social

learning: Rethinking higher education pedagogy in times of systemic global

dysfunction.

Lundegård, I., &

Caiman, C. (2019). Didaktik för naturvetenskap och hållbar utveckling - Fem

former av demokratiskt deltagande. Education for science and Sustainable

Development-Five forms of Democratic Participation. Nordic Studies in Science

Education, 15(1), 38-53. (In Swedish)

Orr, D. (1991) What

is education for?

Osberg, D. and Biesta, G.

(2020). Beyond curriculum: Groundwork for a

non-instrumental theory of education. Educational

Philosophy and Theory.

Stein, S., Andreotti, V.,

Susa, R., Ahenakew, C., and Cajková, T. (2022). From

“education for sustainable development” to “education for the end of the world

as we know it” Educational

Philosophy and Theory, 54(3):274–287

Wilhelm, S., Förster, R.,

& Zimmermann, A. B. (2019). Implementing competence

orientation: Towards constructively aligned education for sustainable

development in university-level teaching-and-learning Sustainability,

11(7), 1891.

Öhman, J., & Östman,

L. (2019). Different teaching traditions in environmental and sustainability

education. In Sustainable Development Teaching (pp. 70-82). Routledge.

Öhman, J., & Sund, L.

(2021). A didactic model of sustainability commitment. Sustainability, 13(6),

3083.