Which sustainability competencies should students obtain in education? That is the question that we have been discussing for the past three weeks as part of the course HEDS241. We have had several articles on sustainability competencies on our reading list, and we had a webinar with professor Marco Rieckmann, University of Vechta. My reflection will be divided into two parts; 1) my own personal review on some sustainable competencies frameworks, and 2) a discussion on the more critical based articles we have been reading.

Competencies for sustainable development

I find the

discussion on which competencies students should obtain very interesting. For

several years I have been reflecting on how we teach this topic, based on

experiences from my own Department but also from stories on how it is often taught

in school. In my opinion there is at present a focus on teaching students about

sustainability issues, but students hardly ever get opportunities to use their

knowledge to do something, to make some action. The reading I have done during

the last few weeks has shown me that the weighting of thinking versus implementation skills is also a discussion that have been

going on among sustainability researchers. Here follows a very brief review on some

of the articles on the reading list concerning competencies:

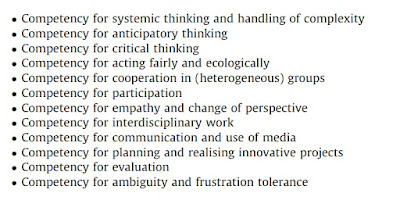

Rieckmann's 12 competencies:

In a Delphi study from 2012 Marco Rieckmann asked 70 experts in education for sustainable development (ESD) from Europe and Latin America about what they meant where the most important competencies for understanding central challenges facing world society and for facilitating development towards a more sustainable future. His results identified 12 key competencies, and among them the three most important were systemic thinking, anticipatory thinking and critical thinking. I found it interesting that several of the competencies in this framework are action competencies; such as being able to act fairly and ecologically, and planning and realizing innovative projects.

Wiek and Brundier

Interestingly,

other researchers have developed frameworks with only ‘thinking’ competencies

and no action competencies, such as in the framework by Wiek et al (2015) where

the following five competencies were identified: systems thinking competency,

interpersonal competency, anticipatory competency, normative competency and

strategic competency. However, in a more recent Delphi study, Brundier et al.

(2021) revise the Wiek et al. framework and include two new competencies;

implementation competency and intrapersonal competency. In the discussion

concerning implementation competency, the authors write that students should

not only learn from stakeholders how they have carried out change, but that

students should “practice it themselves by actually implementing a

sustainability solution in a specifc context, for example, on campus e.g.,

through campus living labs”. According to the authors implementation competency

“catalyzes the cognitively driven integrated problem-solving competency into

manifest changes on the ground” (Brundier et al., 2021).

UNESCO competencies

UNESCO list

eight key competencies for sustainability; systems thinking, anticipatory

competency, normative competency, strategic competency, collaboration

competency, critical thinking competency, self-awareness competency and

integrated problem-solving competency. Although this sounds like purely

cognitive competencies, it is specified that strategic competency also involves

the ability to “develop and implement innovative actions that further

sustainability at the local level and further afield.”

Operationalising the competencies

One thing

is what students should learn, but another thing is how we can operationalize

the competencies. During these two weeks we have also been introduced to some

articles and tools for this. I found the article Operationalising

competencies in higher education for sustainable development (Wiek et al.,

2015) very inspiring. In this article they present three examples of projects

carried out in different student groups, for example a High school in Arizona,

US, that was involved in a group work to improve a neighbouring district with

economic and social problems. In the article they explicitly show how the

various project activities help students develop sustainable competencies, such as

collaboration and systems thinking. We have also been introduced to the web

based tool A rounder sense of purpose, where there are example

activities for how to teach the different competencies, such as the activity Clean

water and sanitation where students address water issues in a systematic

way.

Educator competencies

To be able to teach sustainability competencies, educators will also need a set of competencies. The United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (2012) have identified four central competencies for educators; learning to know, learning to live together, learning to do, and learning to be. In their framework they have specified how the competencies can be implemented in the three essential characteristics of education for sustainable development; holistic approach, envisioning change and achieving transformation.

I still

have a fundamental question after reading and discussing all these competency

frameworks; what is in effect the difference in terms of behavior between a

person with sustainable competence and one who is completely ignorant about

sustainability? It seems to me that universities put a lot of emphasis on

cognitive competencies, but much less emphasis on making people able to use

their knowledge to implement sustainable solutions. Personally, I sometimes wonder

if there is any point in educating people in sustainability at all, if we don’t

expect any change to happen. And this brings me over to the critical

perspective.

Critical perspectives

All the competency frameworks that I have discussed so far can be said to be within a certain view of education, where education is seen an instrument. However, other authors challenge the current view of education and sustainability education. Here I will make an attempt to summarize some of the critical perspectives I have read:

The problem of resilience

Lotz-Sisitka

et al (2015) refers to UNEP reports that show that while society has produced

large amounts of knowledge of global environmental challenges, we do not have

the capacity to respond. Having knowledge of issues is not enough to solve the

problems. The authors also critique the concept of resilience in sustainability

science and learning. They argue that there are many unhealthy systems and

unstainable ways of thinking and acting that are very resilient, such as capitalism.

According to the authors we need action-oriented capabilities, including

development of new modes of learning. These are forms of pedagogy with emphasis

on co-learning, cognitive justice, and formation and development of individual

and systemic agency.

Education as instrument or murmurations

In a philosophical article, Osberg and Biesta (2020) challenge “the mechanic assumption of education” as a “passive instrument that exists primarily to fulfill the purpose(s) of its designer.” They put forward another way of seeing education; something that emerges on its own, and they compare it to how complex bird murmurations is an aestehetic pheonomen that is created by individual birds with no external goal. Osberg & Biesta argue that looking at education as an affective entity in its own right can be seen as an open-ended form of care for the future: “not a ‘good’ future that is already decided in advance”, but “a mode of engagement with an as yet un-manifest future.” It is a bit difficult to see how this can be translated into practical teaching in sustainability, but perhaps it means that future sustainability solutions should emerge as a result of the individual efforts in education.

An education for the end of the world as we know it

Stein et al (2022) turns the issue of sustainable education inside out. They say that instead of asking how we can reorient education to support sustainable development, we should ask what kind of education could prepare people “to face the impossibility of sustaining our contemporary modern-colonial habits of being, which are underwritten by racial, colonial, and ecological violence”. That is; “an education for the end of the world as we know it”. Note that this does not mean the end of the world, only accepting a change in our way of living.

They argue that such an

education involves growing up and showing up. Growing up means being able to interrupt

and limit harmful desires. It emphasizes the disposition to “see and sense

oneself as entangled with and responsible to a wider world/metabolism”, while showing

up is about feeling a commitment to interrupt denials, and to dig deeper to the

root causes of our challenges.

Topic 2 has been a great journey, and I have learnt a lot and got some new perspectives. I have been especially happy to read the critical perspectives, as they resonate with many of the reflections and thoughts that I have had concerning education for sustainable development.

Next week we move on to a new topic: didactic approaches to teaching and learning in education for sustainable development!

Sources:

A Rounder Sense of Purpose (2020).

Brundiers, K., Barth, M., Cebrián, G. et al. (2021) Key competencies in

sustainability in higher education—toward an agreed-upon reference framework. Sustain

Sci 16, 13–29.

Lotz-Sisitka, H., Wals, A. E., Kronlid, D., and McGarry, D. (2015). Transformative, transgressive social learning: Rethinking higher education pedagogy in times of systemic global dysfunction.

Osberg, D. and Biesta, G. (2020). Beyond curriculum: Groundwork for a non-instrumental theory of education. Educational Philosophy and Theory.

Rieckmann,

M. (2012). Future-oriented higher education: Which key competencies should be

fostered through university teaching and learning? Futures, 44(2):127–135.

Special Issue: University Learning

Stein, S., Andreotti, V., Susa, R., Ahenakew, C., and Cajková, T. (2022). From “education for sustainable development” to “education for the end of the world as we know it” Educational Philosophy and Theory, 54(3):274–287

UNESCO

(2017). Education for sustainable

development goals: Learning objectives

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (2012). Learning for the future:

Competences in education for sustainable development

Wiek,

A., Withycombe, L., & Redman, C. L. (2011). Key competencies in

sustainability: a reference framework for academic program development.

Sustainability Science, 6(2), 203–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-011-0132-6

Wiek,

A., Bernstein, M. J., Foley, R. W., Cohen, M., Forrest, N., Kuzdas, C., Kay,

B., and Keeler, L. W. (2015). Operationalising competencies in higher education for sustainable

development In

Routledge handbook of higher education for sustainable development, pages

265–284. Routledge